Degrees without opportunities:

What happens when there are not enough jobs for the highly educated?

Mojca Svetek | 9 April 2024

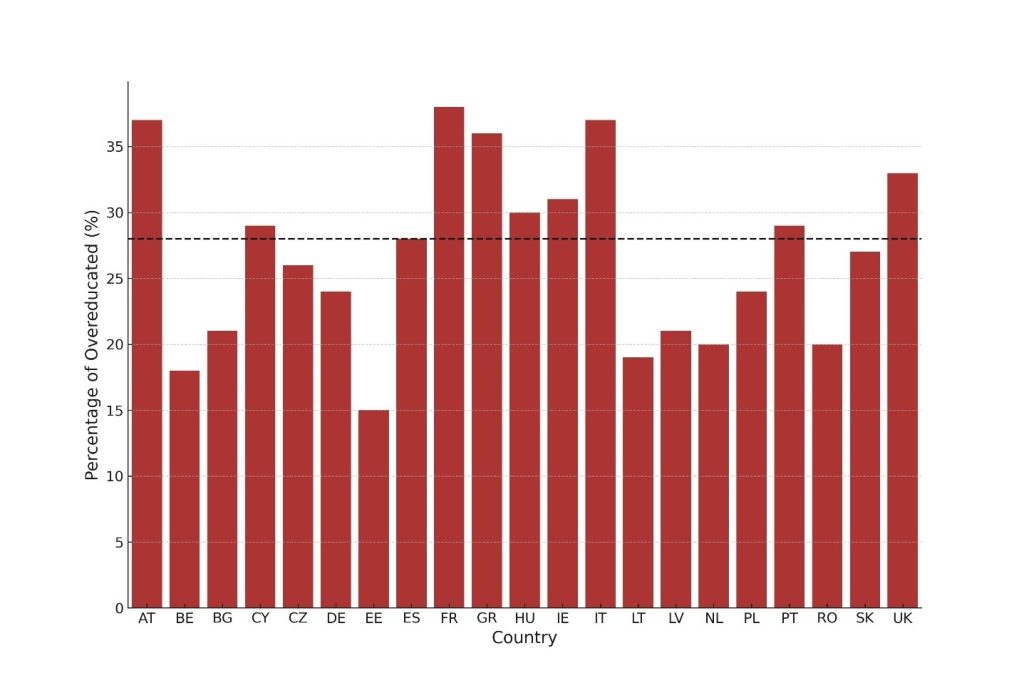

The assumption that the vast majority of tertiary graduates are guaranteed high-skilled jobs no longer seems to apply in many countries. In fact, one in three European workers is overeducated. The problem of underemployment, where people are employed in jobs that require lower levels of education, is projected to increase in many European countries.

Underemployment is not only a problem because underemployed individuals earn lower wages compared to their peers. Underemployment also has long-term consequences on future job prospects of these individuals. In other words, underemployment is individually persistent. This leads to a gradual deterioration of skills and limited skill development. It also negatively affects well-being, especially when individuals feel discouraged about their career prospects.

Looking at it from a policy perspective, it becomes clear that the short-term advantages of quickly entering the workforce can actually lead to long-term disadvantages of being stuck in a job that doesn’t align with one’s qualifications. It is important to note that populations that are more disadvantaged are more likely to experience underemployment and face higher penalties from it. For instance, overqualified women face larger wage penalties compared to overqualified men. This highlights that labour market policies (and possibly educational policies) should strive for achieving a better match between qualifications and job requirements.

While unemployment is widely recognized as detrimental to one’s career prospects, well-being, and health, underemployment is sometimes considered as a solution to unemployment. The question is whether this is a trade-off we should be willing to make? Individuals who take jobs for which they are overeducated indeed remain unemployed for shorter period of time, however in many cases workers may prefer unemployment to underemployment considering that underemployment has a long-term negative consequences for worker’s career developments. Research shows that individuals who do take jobs for which they are overqualified have difficulties breaking out of these jobs. This means that these jobs are not a stepping stone into adequate employment, and these findings replicate over individuals in different stages of life and across different skill groups.

Research articles:

Ahn, N., García, J. R., & Jimeno, J. F. (2004). The impact of unemployment on individual well-being in the EU. European Network of Economic Policy Research Institutes, Working Paper, 29.

Badillo‐Amador, L., & Vila, L. E. (2013). Education and skill mismatches: wage and job satisfaction consequences. International Journal of Manpower.

Baert, S., Cockx, B., & Verhaest, D. (2013). Overeducation at the start of the career: stepping stone or trap? Labour Economics, 25, 123-140.

Eurostat. (2016). EU labour force survey. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey

Green, F., & Henseke, G. (2021). Europe’s evolving graduate labour markets: supply, demand, underemployment and pay. Journal for Labour Market Research, 55(1), 1-13.

Heyes, J., & Tomlinson, M. (2021). Underemployment and well-being in Europe. Human Relations, 74(8), 1240-1266.

Iriondo, I., & Pérez-Amaral, T. (2016). The effect of educational mismatch on wages in Europe. Journal of Policy Modeling, 38(2), 304-323.

McGuinness, S., Bergin, A., & Whelan, A. (2018). Overeducation in Europe: trends, convergence, and drivers. Oxford Economic Papers, 70(4), 994-1015.

Rossen, A., Boll, C., & Wolf, A. (2019). Patterns of overeducation in Europe: The role of field of study. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 9(1), 1-48.

Salinas-Jiménez, M. d. M., Rahona-López, M., & Murillo-Huertas, I. P. (2013). Gender wage differentials and educational mismatch: an application to the Spanish case. Applied Economics, 45(30), 4226-4235.

Voßemer, J., & Schuck, B. (2015). Better overeducated than unemployed? The short-and long-term effects of an overeducated labour market re-entry. European Sociological Review, 32(2), 251-265.

Next article