Entrepreneurs vs. corporations: Who creates (good) jobs?

Mojca Svetek | 9 January 2024

Entrepreneurship is often praised for its significant contributions to innovation, economic growth, and the reduction of unemployment. These three concepts are actually tightly related. Innovation, encompassing both technological advancements and process improvements, plays a crucial role in driving economic growth by enhancing productivity. And when an economy grows, unemployment tends to decrease. In 1960s American economist Art Okun was first to observe that a country’s GDP must grow at about 2% faster than expected for one year to achieve a 1% reduction in the rate of unemployment. This finding is known in economics as Okun’s law.

While policymakers are committed to support young and small companies, a pertinent question arises: Which companies are capable of not just generating new jobs, but also fostering the creation of good jobs?

Which companies create new jobs?

In understanding the intricacies of job creation within an economy, it is crucial to move beyond the conventional classification of firms based solely on size. Distinguishing between big and small companies is a starting point, but it is equally important to differentiate between young and mature firms.

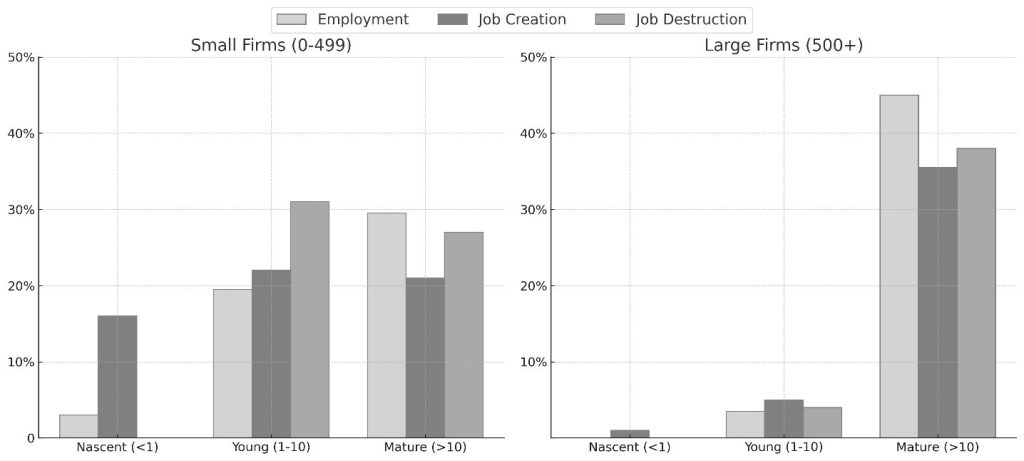

Less than 1% of firms in the EU and US are large, mature companies, yet they provide 35% to 45% of all jobs. The remaining 99% of firms is small – most of them are mature, some of them are young – together supplying the remaining 55-65 % of jobs.

However, the job market is dynamic. New jobs open, old jobs close, most of them endure. Assessing job creation capacity goes beyond initial job numbers. It requires accounting for number of jobs created and number of jobs destroyed by different types of companies.

As a rule of thumb, the share of jobs created and destroyed by different groups of firms is somewhat related to the share of total employment provided by these firms. To illustrate, large, mature companies contribute 45% of US jobs, create 35% of new jobs, and account for 40% of job losses. Similarly, small, mature firms offer 30% of jobs, create 20% of new jobs, and cause 30% of lost jobs. Despite employing the majority of workers and producing about 55% of new jobs, mature companies (big and small) are still net job destroyers. Job growth is singlehandedly driven by young companies, specifically those aiming to become large enterprises (even though 40-50% of them fail within the first few years, resulting in the loss of previously created jobs).

Which companies create good jobs?

This brings me to quality of these jobs. Net job creation of entrepreneurs goes along with a relatively high job destruction rate as almost half of new firms fail within their first five years. Despite the expectation that younger firms would offer higher wages to compensate for the high job insecurity, studies on firm size wage differentials consistently find that smaller and younger firms actually pay lower wages to their employees.

Smaller and younger firms are more likely to hire individuals who face labour market disadvantages. These individuals, including those with limited experience, lower levels of education, and who belong to marginalized groups, are often hired at lower costs. Taking up a position at a startup may not be the optimal financial choice. Research demonstrates that startup employees earn significantly less in the long run, especially if a startup fails and they experience a period of unemployment. Additionally, former startup employees often pursue their next job opportunity within another startup or a small firm.

Despite all objective indicators suggesting that entrepreneurs offer worse jobs than corporations, employees in small firms tend to report higher levels of job satisfaction. The primary reason for this is the better relationships they develop with their bosses, other reasons include higher autonomy and a sense of achievement.

This indicates that despite entrepreneurs offering worse jobs in terms of stability and pay compared to corporations, they are able to keep the morale of employees high.

Research articles:

Bogliacino, F., & Pianta, M. (2011). Engines of growth. Innovation and productivity in industry groups. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 22(1), 41-53.

Brown, C., & Medoff, J. L. (2003). Firm age and wages. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(3), 677-697.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347-361.

Looze, J. & Goff, T. (2022). Job creation by firm age: Recent trends in the United States. Kauffman Foundation.

Okun, A. M. (1983). Economics for policymaking: Selected essays of Arthur M. Okun. MIT Press Books.

Sorenson, O., Dahl, M. S., Canales, R., & Burton, M. D. (2021). Do startup employees earn more in the long run?. Organization Science, 32(3), 587-604.

Tansel, A., & Gazîoğlu, Ş. (2014). Management-employee relations, firm size and job satisfaction. International journal of manpower, 35(8), 1260-1275.

Van Praag, C. M., & Versloot, P. H. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small business economics, 29(4), 351-382.