Is a bad job better than no job at all?

Mojca Svetek | 12 December 2023

We know that unemployment is bad. It is bad for the unemployed. Long term unemployment increases risk to health by up to 132 %. The negative effects of unemployment are not only due to its impact on material circumstances, but also stem from widely recognized social and psychological functions of employment.

To function properly, people need work.

Work provides (1) time structure, (2) meaningful activity, (3) it shapes how one perceives themselves and how others perceive them (status and identity), (4) it furnishes feeling of being useful to others (collective purpose) and fosters (5) social contact outside the family. This is in addition to income and monetary rewards.

But that doesn’t mean that any job is better than no job. In fact, research shows that poor-quality jobs, characterized by multiple stressors, especially job insecurity, are just as damaging to physical and mental health as is unemployment.

Jobs can come with various psychosocial stressors. First, there is job strain, which is a combination of excessive job demands and insufficient resources to effectively handle those demands. The second stressor is job insecurity, this is the anticipation of losing one’s job. Lastly, there’s the lack of employment opportunities outside of one’s current job. While some jobs come with every one of these stressors, other come with none.

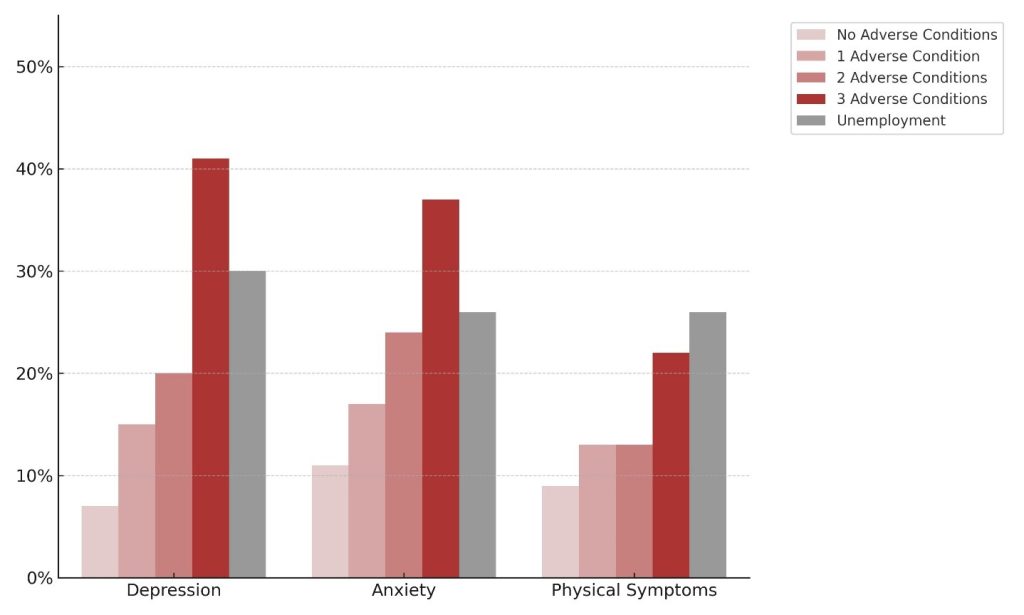

Research is clear: more stressors, poorer mental and psychical health. This is not surprising. The key finding is that individuals facing all three stressors fare no better than the unemployed. What is more, those who transition from unemployment to an insecure, low-quality job typically report worsened, not improved, mental health. This suggests that employment sometimes results in worse outcomes than unemployment.

As much as economists and policy makers fear high unemployment rates and seek ways to reduce it, low quality jobs may not be the answer we are looking for. The challenge lies in the relationships between work, health and job quality. They actually reinforce each other. Unemployed with poorest physical and mental health have the poorest employment opportunities. If they manage to transition into employment, they often find themselves in low-quality, insecure jobs that further deteriorate their well-being and expose them to the risk of subsequent unemployment. However, those who successfully transition from unemployment to high-quality jobs report significant improvements in their overall health, particularly in terms of mental well-being.

The health benefits of employment are associated with job quality and not employment per se. So, any far-sighted labour market policy must place equal emphasis on the quality of employment opportunities as it does on their availability, if it seeks to achieve sustainable results.

Research articles:

Broom, D. H., D’souza, R. M., Strazdins, L., Butterworth, P., Parslow, R., & Rodgers, B. (2006). The lesser evil: bad jobs or unemployment? A survey of mid-aged Australians. Social science & medicine, 63(3), 575-586.

del Amo González, M. P. L., Benítez, V., & Martín-Martín, J. J. (2018). Long term unemployment, income, poverty, and social public expenditure, and their relationship with self-perceived health in Spain (2007–2011). BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1-14.

Kim, T. J., & von Dem Knesebeck, O. (2015). Is an insecure job better for health than having no job at all? A systematic review of studies investigating the health-related risks of both job insecurity and unemployment. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1-9.

Leach, L. S., Butterworth, P., Strazdins, L., Rodgers, B., Broom, D. H., & Olesen, S. C. (2010). The limitations of employment as a tool for social inclusion. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 1-13.

Paul, K. I., & Batinic, B. (2010). The need for work: Jahoda’s latent functions of employment in a representative sample of the German population. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(1), 45-64.