The promise of flexicurity:

Can employability and income security really offset the negative effects of job insecurity?

Mojca Svetek | 14 May 2024

The idea of flexicurity has a great appeal to policy makers. It promises that it is possible to simultaneously provide organisations with greater flexibility and offer workers the necessary level of security. This is achieved by replacing job security – which stems from permanent employment contracts and employment protection legislation – with better employability of workforce and income protection in the periods of unemployment. Apparently, this sounds good to many policymakers and employers but does it work?

Job insecurity is first and foremost stressful. Most of this stress arises from the uncertainty over job continuity and potential income loss. To counter that employability is advocated as a key career success factor in a context where job security and stable employment are no longer guaranteed. Employability is not only a factor in shortening the duration of unemployment. Employable individuals are also less anxious over losing one’s job. If the negative effects of job insecurity are due to fear of losing income from employment, greater employability together with generous unemployment benefits should work well to counter that.

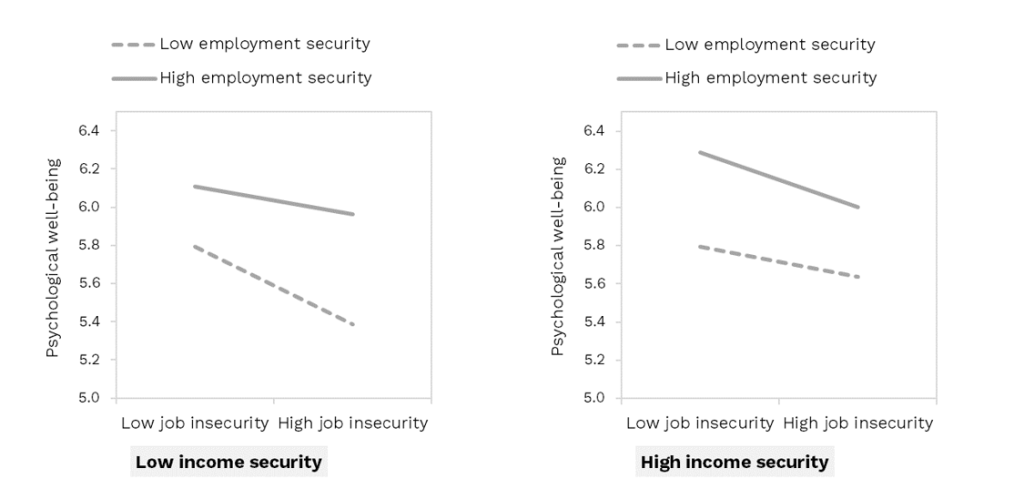

Studies that looked into whether employability and income security can mitigate the negative effects of job insecurity on psychological well-being and job satisfaction failed to find expected results. While employment security and income security might promote a sense of well-being they (separately or jointly) are not able to compensate for the lack of job security.

People get much more out of their jobs than just an income. Jobs give people a sense of purpose, a sense of being needed by others, a sense of being useful, a sense of identity, and hopefully a good social status in a society. Job insecurity therefore threatens much more than just income. In addition, many people perceive job insecurity as unfair and exploitative. People tend to compare themselves to others. Employees in insecure jobs perceive inequity compared to co-workers and peers in similar but secure jobs, leading to greater job and life dissatisfaction.

Based on these findings, policy-makers should not count on employability and more extensive unemployment benefits to buffer the negative consequences of job insecurity. Rather, they should focus on preventing job insecurity in the first place.

Research articles:

Berglund, T., Furåker, B., & Vulkan, P. (2014). Is job insecurity compensated for by employment and income security? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 35(1), 165-184.

Chiesa, R., Fazi, L., Guglielmi, D., & Mariani, M. G. (2018). Enhancing substainability: Psychological capital, perceived employability, and job insecurity in different work contract conditions. Sustainability, 10(7), paper no. 2475.

European Commission. (n.d.). Flexicurity. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=102&langId=en

Jahoda, M. (1982). Employment and unemployment. Cambridge Books.

Leka, S. & Jain, A. (2010). Health Impact of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: An Overview. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Svetek, M. (2022). The promise of flexicurity: Can employment and income security mitigate the negative effects of job insecurity? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 43(3), 1206-1235.

Wilthagen, T. & Tros, F. (2004). The concept of ‘flexicurity’: a new approach to regulating employment and labour markets. Transfer: European Review of labour and research, 10(2), 166-186.

Previous article